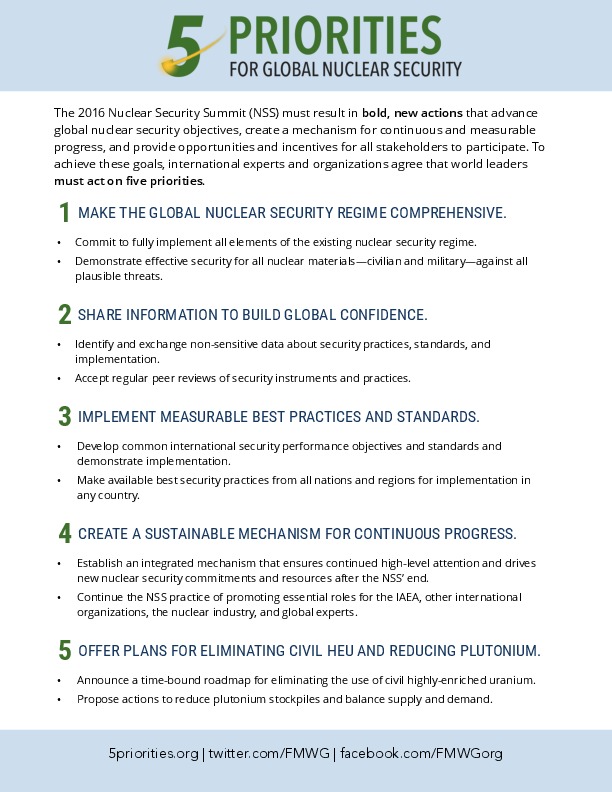

If we want real, long-term nuclear security, we need an international agreement that addresses all five of these common-sense criteria.

comprehensive | open | rigorous | sustainable | reduced

1. Comprehensive

With dangerous nuclear materials, there is no margin for error. Wherever there’s a gap in the policy or a mistake in security or safety practices, there’s the potential for misuse—and catastrophic consequences.

We can’t take our chances with partial solutions; we need a comprehensive, global agreement that covers all of the dangerous nuclear materials in the world.

We need a set of rules that apply to everyone: the smallest countries and the largest, the military and civilians alike. We need to create the expectation that every country will apply all of the internationally-agreed-upon standards.

We can’t afford anything less. Check out what two former ambassadors have said about this idea in the Washington Post.

2. Open

Global challenges like terrorism threaten all of us, no matter where we live. A Cold War mentality, obsessed with excessive secrecy, doesn’t make sense in the 21st century.

While countries must keep some highly sensitive information about their nuclear practices out of the public eye, there’s plenty that they can share to make the public safer without compromising national security.

Sharing non-sensitive information allows citizens to hold their leaders accountable, and it helps other nations to see what works, where they can make improvements, and how they can cooperate. There needs to be public confidence in global security practices and assurances that these standards are being reviewed regularly by experts to ensure safety and efficiency.

3. Rigorous

We need a set of measurable standards for all countries. It’s shocking that more than 70 years after the introduction of nuclear technology we still don’t have a common set of objectives and goals for nuclear security among countries.

Best practices for keeping nuclear materials secure don’t belong to any one country. Plutonium doesn’t really care whether it’s in the United States, the Ukraine, Uruguay, or Uzbekistan; if it’s not handled properly, it’s dangerous everywhere. Everyone benefits when we share best standards and practices for keeping nuclear materials safe.

4. Sustainable

The 2016 summit can’t be the last word.

We need an international framework that can address new developments in information, technology, and security. The systems must be adaptable and bring the very latest resources to bear.

We need a framework that will keep bringing together the very best experts and national leaders. It should keep this issue front and center and encourage new actions when new threats and opportunities arise.

We need to make sure that the people who will be implementing these agreements—the nuclear industry, groups like the International Atomic Energy Agency, and nuclear security experts—are collaborating with each other and benefit from new developments in various fields.

In other words, we need to agree that 2016 is just the beginning of an ongoing, sustainable process to keep us safe in the long term.

5. Reduced

While agreements to manage and secure nuclear materials in the short term are incredibly important, the only long-term solution is to get rid of the most dangerous material, like civil highly-enriched uranium and huge stockpiles of excess plutonium. These materials can be used to make nuclear weapons or dirty bombs.

Every ounce of that material that is converted to something less dangerous is one less ounce that could end up in the hands of terrorists or criminals.

Eventually, these dangerous materials shouldn’t be in the hands of civilians at all—and militaries also need to reduce their stockpiles.

We need a long-term plan to ensure this becomes a reality.

The 2016 Nuclear Security Summit

In 2010, U.S. President Barack Obama launched the Nuclear Security Summit (NSS) process, inviting dozens of heads of states to Washington, DC, to discuss nuclear security. Additional summits were held in Seoul, Republic of Korea (2012), and in The Hague, Netherlands (2014). The summits have brought high-level attention to the issue of protecting vulnerable nuclear and other radioactive materials, which has resulted in actions that made the world a safer place for people across every continent.

However, the mission is not yet complete. With the final summit coming up in 2016, it is imperative that the NSS process results in a legacy that will sustain achievements and close remaining gaps in the global nuclear security architecture. While additional summits may be planned, they are unlikely to be of the same scope, scale, and frequency. The world leaders participating in the 2016 NSS must not let this opportunity slip by.

Dutch

Dutch English

English French

French German

German Korean

Korean Russian

Russian Spanish

Spanish Swedish

Swedish Turkish

Turkish